Bird

For other uses, see Bird (disambiguation).

Aves and Avifauna redirect here. For other uses, see Aves (disambiguation) or Avifauna (disambiguation).

| Birds Temporal range: Late Jurassic–Recent, 150–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| The diversity of modern birds. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Class: | Aves Linnaeus, 1758[1] |

| Subclasses | |

| And see text | |

Modern birds are characterised by feathers, a beak with no teeth, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a lightweight but strong skeleton. All living species of birds have wings- the most recent species without wings was the moa, which is generally considered to have become extinct in the 1500s. Wings are evolved forelimbs, and most bird species can fly. Flightless birds include ratites, penguins, and a number of diverse endemic island species. Birds also have unique digestive and respiratory systems that are highly adapted for flight. Some birds, especially corvids and parrots, are among the most intelligent animal species; a number of bird species have been observed manufacturing and using tools, and many social species exhibit cultural transmission of knowledge across generations.

Many species undertake long distance annual migrations, and many more perform shorter irregular movements. Birds are social; they communicate using visual signals and through calls and songs, and participate in social behaviours, including cooperative breeding and hunting, flocking, and mobbing of predators. The vast majority of bird species are socially monogamous, usually for one breeding season at a time, sometimes for years, but rarely for life. Other species have polygynous ("many females") or, rarely, polyandrous ("many males") breeding systems. Eggs are usually laid in a nest and incubated by the parents. Most birds have an extended period of parental care after hatching.

Many species are of economic importance, mostly as sources of food acquired through hunting or farming. Some species, particularly songbirds and parrots, are popular as pets. Other uses include the harvesting of guano (droppings) for use as a fertiliser. Birds figure prominently in all aspects of human culture from religion to poetry to popular music. About 120–130 species have become extinct as a result of human activity since the 17th century, and hundreds more before then. Currently about 1,200 species of birds are threatened with extinction by human activities, though efforts are underway to protect them.

Contents[hide] |

Evolution and taxonomy

Main article: Evolution of birds

| ||||||||||||||||||

| The birds' phylogenetic relationships to major living reptile groups. |

All modern birds lie within the crown group Neornithes, which has two subdivisions: the Palaeognathae, which includes the flightless ratites (such as the ostriches) and the weak-flying tinamous, and the extremely diverse Neognathae, containing all other birds.[4] These two subdivisions are often given the rank of superorder,[7] although Livezey and Zusi assigned them "cohort" rank.[4] Depending on the taxonomic viewpoint, the number of known living bird species varies anywhere from 9,800[8] to 10,050.[9]

Dinosaurs and the origin of birds

Main article: Origin of birds

The consensus view in contemporary paleontology is that the birds, or avialans, are the closest relatives of the deinonychosaurs, which include dromaeosaurids, troodontids and possibly archaeopterygids.[13] Together, these three form a group called Paraves. Some basal members of this group, such as Microraptor and Archaeopteryx, have features which may have enabled them to glide or fly. The most basal deinonychosaurs are very small. This evidence raises the possibility that the ancestor of all paravians may have been arboreal, may have been able to glide, or both.[14][15] Unlike Archaeopteryx and the feathered dinosaurs, who primarily ate meat, recent studies suggest that the first birds were herbivores.[16]

The Late Jurassic Archaeopteryx is well known as one of the first transitional fossils to be found, and it provided support for the theory of evolution in the late 19th century. Archaeopteryx was the first fossil to display both clearly reptilian characteristics: teeth, clawed fingers, and a long, lizard-like tail, as well as wings with flight feathers identical to those of modern birds. It is not considered a direct ancestor of modern birds, though it is possibly closely related to the real ancestor.[17]

Alternative theories and controversies

Early disagreements on the origins of birds included whether birds evolved from dinosaurs or more primitive archosaurs. Within the dinosaur camp, there were disagreements as to whether ornithischian or theropod dinosaurs were the more likely ancestors.[18] Although ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs share the hip structure of modern birds, birds are thought to have originated from the saurischian (lizard-hipped) dinosaurs, and therefore evolved their hip structure independently.[19] In fact, a bird-like hip structure evolved a third time among a peculiar group of theropods known as the Therizinosauridae.A small minority of researchers, such as paleornithologist Alan Feduccia of the University of North Carolina, challenge the majority view, contending that birds are not dinosaurs, but evolved from early archosaurs like Longisquama.[20][21]

Early evolution of birds

See also: List of fossil birds

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basal bird phylogeny simplified after Chiappe, 2007[22] |

The first large, diverse lineage of short-tailed birds to evolve were the Enantiornithes, or "opposite birds", so named because the construction of their shoulder bones was in reverse to that of modern birds. Enantiornithes occupied a wide array of ecological niches, from sand-probing shorebirds and fish-eaters to tree-dwelling forms and seed-eaters.[22]

Many species of the second major bird lineage to diversify, the Ornithurae (including the ancestors of modern birds), specialised in eating fish, like the superficially gull-like subclass Ichthyornithes (fish birds).[24] One order of Mesozoic seabirds, the Hesperornithiformes, became so well adapted to hunting fish in marine environments, they lost the ability to fly and became primarily aquatic. Despite their extreme specializations, the Hesperornithiformes represent some of the closest relatives of modern birds.[22]

Diversification of modern birds

See also: Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy and dinosaur classification

Containing all modern birds, the subclass Neornithes is, due to the discovery of Vegavis, now known to have evolved into some basic lineages by the end of the Cretaceous[25] and is split into two superorders, the Palaeognathae and Neognathae. The paleognaths include the tinamous of Central and South America and the ratites. The basal divergence from the remaining Neognathes was that of the Galloanserae, the superorder containing the Anseriformes (ducks, geese, swans and screamers) and the Galliformes (the pheasants, grouse, and their allies, together with the mound builders and the guans and their allies). The dates for the splits are much debated by scientists. The Neornithes are agreed to have evolved in the Cretaceous, and the split between the Galloanseri from other Neognathes occurred before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, but there are different opinions about whether the radiation of the remaining Neognathes occurred before or after the extinction of the other dinosaurs.[26] This disagreement is in part caused by a divergence in the evidence; molecular dating suggests a Cretaceous radiation, while fossil evidence supports a Tertiary radiation. Attempts to reconcile the molecular and fossil evidence have proved controversial.[26][27]The classification of birds is a contentious issue. Sibley and Ahlquist's Phylogeny and Classification of Birds (1990) is a landmark work on the classification of birds,[28] although it is frequently debated and constantly revised. Most evidence seems to suggest the assignment of orders is accurate,[29] but scientists disagree about the relationships between the orders themselves; evidence from modern bird anatomy, fossils and DNA have all been brought to bear on the problem, but no strong consensus has emerged. More recently, new fossil and molecular evidence is providing an increasingly clear picture of the evolution of modern bird orders.

Classification of modern bird orders

See also: List of birds

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basal divergences of modern birds based on Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy |

Subclass Neornithes

The subclass Neornithes has two extant superorders –

Superorder Palaeognathae:

The name of the superorder is derived from paleognath, the ancient Greek for "old jaws" in reference to the skeletal anatomy of the palate, which is described as more primitive and reptilian than that in other birds. The Palaeognathae consists of two orders which comprise 49 existing species.

- Struthioniformes—ostriches, emus, kiwis, and allies

- Tinamiformes—tinamous

The superorder Neognathae comprises 27 orders which have a total of nearly ten thousand species. The Neognathae have undergone adaptive radiation to produce the staggering diversity of form (especially of the bill and feet), function, and behaviour that are seen today.

The orders comprising the Neognathae are:

- Anseriformes—waterfowl

- Galliformes—fowl

- Charadriiformes—gulls, button-quails, plovers and allies

- Gaviiformes—loons

- Podicipediformes—grebes

- Procellariiformes—albatrosses, petrels, and allies

- Sphenisciformes—penguins

- Pelecaniformes—pelicans and allies

- Phaethontiformes—tropicbirds

- Ciconiiformes—storks and allies

- Cathartiformes—New World vultures

- Phoenicopteriformes—flamingos

- Falconiformes—falcons, eagles, hawks and allies

- Gruiformes—cranes and allies

- Pteroclidiformes—sandgrouse

- Columbiformes—doves and pigeons

- Psittaciformes—parrots and allies

- Cuculiformes—cuckoos and turacos

- Opisthocomiformes—hoatzin

- Strigiformes—owls

- Caprimulgiformes—nightjars and allies

- Apodiformes—swifts and hummingbirds

- Coraciiformes—kingfishers and allies

- Piciformes—woodpeckers and allies

- Trogoniformes—trogons

- Coliiformes—mousebirds

- Passeriformes—passerines

Distribution

See also: Lists of birds by region

Many bird species have established breeding populations in areas to which they have been introduced by humans. Some of these introductions have been deliberate; the Ring-necked Pheasant, for example, has been introduced around the world as a game bird.[36] Others have been accidental, such as the establishment of wild Monk Parakeets in several North American cities after their escape from captivity.[37] Some species, including Cattle Egret,[38] Yellow-headed Caracara[39] and Galah,[40] have spread naturally far beyond their original ranges as agricultural practices created suitable new habitat.

Anatomy and physiology

Main articles: Bird anatomy and Bird vision

External anatomy of a bird (example: Yellow-wattled Lapwing): 1 Beak, 2 Head, 3 Iris, 4 Pupil, 5 Mantle, 6 Lesser coverts, 7 Scapulars, 8 Median coverts, 9 Tertials, 10 Rump, 11 Primaries, 12 Vent, 13 Thigh, 14 Tibio-tarsal articulation, 15 Tarsus, 16 Foot, 17 Tibia, 18 Belly, 19 Flanks, 20 Breast, 21 Throat, 22 Wattle

The skeleton consists of very lightweight bones. They have large air-filled cavities (called pneumatic cavities) which connect with the respiratory system.[41] The skull bones in adults are fused and do not show cranial sutures.[42] The orbits are large and separated by a bony septum. The spine has cervical, thoracic, lumbar and caudal regions with the number of cervical (neck) vertebrae highly variable and especially flexible, but movement is reduced in the anterior thoracic vertebrae and absent in the later vertebrae.[43] The last few are fused with the pelvis to form the synsacrum.[42] The ribs are flattened and the sternum is keeled for the attachment of flight muscles except in the flightless bird orders. The forelimbs are modified into wings.[44]

Like the reptiles, birds are primarily uricotelic, that is, their kidneys extract nitrogenous wastes from their bloodstream and excrete it as uric acid instead of urea or ammonia via the ureters into the intestine. Birds do not have a urinary bladder or external urethral opening and (with exception of the Ostrich) uric acid is excreted along with feces as a semisolid waste.[45][46][47] However, birds such as hummingbirds can be facultatively ammonotelic, excreting most of the nitrogenous wastes as ammonia.[48] They also excrete creatine, rather than creatinine like mammals.[42] This material, as well as the output of the intestines, emerges from the bird's cloaca.[49][50] The cloaca is a multi-purpose opening: waste is expelled through it, birds mate by joining cloaca, and females lay eggs from it. In addition, many species of birds regurgitate pellets.[51] The digestive system of birds is unique, with a crop for storage and a gizzard that contains swallowed stones for grinding food to compensate for the lack of teeth.[52] Most birds are highly adapted for rapid digestion to aid with flight.[53] Some migratory birds have adapted to use protein from many parts of their bodies, including protein from the intestines, as additional energy during migration.[54]

Birds have one of the most complex respiratory systems of all animal groups.[42] Upon inhalation, 75% of the fresh air bypasses the lungs and flows directly into a posterior air sac which extends from the lungs and connects with air spaces in the bones and fills them with air. The other 25% of the air goes directly into the lungs. When the bird exhales, the used air flows out of the lung and the stored fresh air from the posterior air sac is simultaneously forced into the lungs. Thus, a bird's lungs receive a constant supply of fresh air during both inhalation and exhalation.[55] Sound production is achieved using the syrinx, a muscular chamber incorporating multiple tympanic membranes which diverges from the lower end of the trachea;[56] the trachea being elongated in some species, increasing the volume of vocalizations and the perception of the bird's size.[57] The bird's heart has four chambers like a mammalian heart. In birds the main arteries taking blood away from the heart originate from the right aortic arch (or pharyngeal arch), unlike in the mammals where the left aortic arch forms this part of the aorta.[42] The postcava receives blood from the limbs via the renal portal system. Unlike in mammals, the circulating red blood cells in birds retain their nucleus.[58]

A few species are able to use chemical defenses against predators; some Procellariiformes can eject an unpleasant oil against an aggressor,[69] and some species of pitohuis from New Guinea have a powerful neurotoxin in their skin and feathers.[70]

Chromosomes

Birds have two sexes: male and female. The sex of birds is determined by the Z and W sex chromosomes, rather than by the X and Y chromosomes present in mammals. Male birds have two Z chromosomes (ZZ), and female birds have a W chromosome and a Z chromosome (WZ).[42]In nearly all species of birds, an individual's sex is determined at fertilization. However, one recent study demonstrated temperature-dependent sex determination among Australian Brush-turkeys, for which higher temperatures during incubation resulted in a higher female-to-male sex ratio.[71]

Feathers, plumage, and scales

Main articles: Feather and Flight feather

Plumage is regularly moulted; the standard plumage of a bird that has moulted after breeding is known as the "non-breeding" plumage, or—in the Humphrey-Parkes terminology—"basic" plumage; breeding plumages or variations of the basic plumage are known under the Humphrey-Parkes system as "alternate" plumages.[74] Moulting is annual in most species, although some may have two moults a year, and large birds of prey may moult only once every few years. Moulting patterns vary across species. In passerines, flight feathers are replaced one at a time with the innermost primary being the first. When the fifth of sixth primary is replaced, the outermost tertiaries begin to drop. After the innermost tertiaries are moulted, the secondaries starting from the innermost begin to drop and this proceeds to the outer feathers (centrifugal moult). The greater primary coverts are moulted in synchrony with the primary that they overlap.[75] A small number of species, such as ducks and geese, lose all of their flight feathers at once, temporarily becoming flightless.[76] As a general rule, the tail feathers are moulted and replaced starting with the innermost pair.[75] Centripetal moults of tail feathers are however seen in the Phasianidae.[77] The centrifugal moult is modified in the tail feathers of woodpeckers and treecreepers, in that it begins with the second innermost pair of feathers and finishes with the central pair of feathers so that the bird maintains a functional climbing tail.[75][78] The general pattern seen in passerines is that the primaries are replaced outward, secondaries inward, and the tail from center outward.[79] Before nesting, the females of most bird species gain a bare brood patch by losing feathers close to the belly. The skin there is well supplied with blood vessels and helps the bird in incubation.[80]

The scales of birds are composed of the same keratin as beaks, claws, and spurs. They are found mainly on the toes and metatarsus, but may be found further up on the ankle in some birds. Most bird scales do not overlap significantly, except in the cases of kingfishers and woodpeckers. The scales of birds are thought to be homologous to those of reptiles and mammals.[84]

Flight

Main article: Bird flight

Behaviour

Most birds are diurnal, but some birds, such as many species of owls and nightjars, are nocturnal or crepuscular (active during twilight hours), and many coastal waders feed when the tides are appropriate, by day or night.[88]Diet and feeding

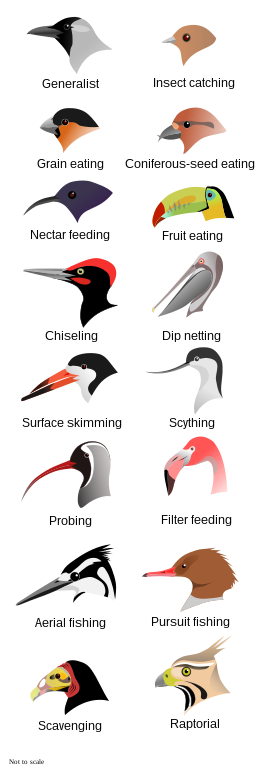

Birds' diets are varied and often include nectar, fruit, plants, seeds, carrion, and various small animals, including other birds.[42] Because birds have no teeth, their digestive system is adapted to process unmasticated food items that are swallowed whole.Birds that employ many strategies to obtain food or feed on a variety of food items are called generalists, while others that concentrate time and effort on specific food items or have a single strategy to obtain food are considered specialists.[42] Birds' feeding strategies vary by species. Many birds glean for insects, invertebrates, fruit, or seeds. Some hunt insects by suddenly attacking from a branch. Those species that seek pest insects are considered beneficial 'biological control agents' and their presence encouraged in biological pest control programs.[89] Nectar feeders such as hummingbirds, sunbirds, lories, and lorikeets amongst others have specially adapted brushy tongues and in many cases bills designed to fit co-adapted flowers.[90] Kiwis and shorebirds with long bills probe for invertebrates; shorebirds' varied bill lengths and feeding methods result in the separation of ecological niches.[42][91] Loons, diving ducks, penguins and auks pursue their prey underwater, using their wings or feet for propulsion,[34] while aerial predators such as sulids, kingfishers and terns plunge dive after their prey. Flamingos, three species of prion, and some ducks are filter feeders.[92][93] Geese and dabbling ducks are primarily grazers.

Some species, including frigatebirds, gulls,[94] and skuas,[95] engage in kleptoparasitism, stealing food items from other birds. Kleptoparasitism is thought to be a supplement to food obtained by hunting, rather than a significant part of any species' diet; a study of Great Frigatebirds stealing from Masked Boobies estimated that the frigatebirds stole at most 40% of their food and on average stole only 5%.[96] Other birds are scavengers; some of these, like vultures, are specialised carrion eaters, while others, like gulls, corvids, or other birds of prey, are opportunists.[97]

Water and drinking

Water is needed by many birds although their mode of excretion and lack of sweat glands reduces the physiological demands.[98] Some desert birds can obtain their water needs entirely from moisture in their food. They may also have other adaptations such as allowing their body temperature to rise, saving on moisture loss from evaporative cooling or panting.[99] Seabirds can drink seawater and have salt glands inside the head that eliminate excess salt out of the nostrils.[100]Most birds scoop water in their beaks and raise their head to let water run down the throat. Some species, especially of arid zones, belonging to the pigeon, finch, mousebird, button-quail and bustard families are capable of sucking up water without the need to tilt back their heads.[101] Some desert birds depend on water sources and sandgrouse are particularly well known for their daily congregations at waterholes. Nesting sandgrouse and many plovers carry water to their young by wetting their belly feathers.[102] Some birds carry water for chicks at the nest in their crop or regurgitate it along with food. The pigeon family, flamingos and penguins have adaptations to produce a nutritive fluid called crop milk that they provide to their chicks.[103]

Bathing and dusting

A bird bathes by wetting its feathers using any of a variety of techniques.- Wading involves birds standing in water and fluffing their feathers and flicking their wings in and out of the water. The birds also roll their breasts on the surfacing of the water and then flick their heads back in order to throw water on the feathers of the back. Robins, thrushes, mockingbirds, jays, and titmice have been observed to use this bathing technique.

- Dipping – Some birds dip into water during flight, wetting their wings. The tail is used to direct the spray of the water unto the back. Swifts and swallows have been observed to use this bathing technique.

- Some birds dart repeated into water, quickly immersing and rolling through the water. They vibrate their feathers after each dart. Chickadees, yellowthroats, wrens, buntings, and waterthrushes have displayed this bathing behavior.

- In areas where there is a scarcity of water, birds such as the wrentit, wet their feathers with the dew from vegetation.

- Especially in arid areas birds use dusting instead of water bathing. Birds rake the dust from the ground and then cast the dust over their bodies. The dust is also to settle on the feathers and then shaken off. Wrens, House Sparrows, Wrentits, larks have been observed to use dusting.

- Other birds perform a more passive form of bathing, extending their wings and tails during light drizzles so that their feathers are wet. Woodpeckers and nuthatches practice this method of bathing.

Migration

Main article: Bird migration

Many bird species migrate to take advantage of global differences of seasonal temperatures, therefore optimising availability of food sources and breeding habitat. These migrations vary among the different groups. Many landbirds, shorebirds, and waterbirds undertake annual long distance migrations, usually triggered by the length of daylight as well as weather conditions. These birds are characterised by a breeding season spent in the temperate or arctic/antarctic regions and a non-breeding season in the tropical regions or opposite hemisphere. Before migration, birds substantially increase body fats and reserves and reduce the size of some of their organs.[54][105] Migration is highly demanding energetically, particularly as birds need to cross deserts and oceans without refuelling. Landbirds have a flight range of around 2,500 km (1,600 mi) and shorebirds can fly up to 4,000 km (2,500 mi),[106] although the Bar-tailed Godwit is capable of non-stop flights of up to 10,200 km (6,300 mi).[107] Seabirds also undertake long migrations, the longest annual migration being those of Sooty Shearwaters, which nest in New Zealand and Chile and spend the northern summer feeding in the North Pacific off Japan, Alaska and California, an annual round trip of 64,000 km (39,800 mi).[108] Other seabirds disperse after breeding, travelling widely but having no set migration route. Albatrosses nesting in the Southern Ocean often undertake circumpolar trips between breeding seasons.[109]

The routes of satellite-tagged Bar-tailed Godwits migrating north from New Zealand. This species has the longest known non-stop migration of any species, up to 10,200 km (6,300 mi).

The ability of birds to return to precise locations across vast distances has been known for some time; in an experiment conducted in the 1950s a Manx Shearwater released in Boston returned to its colony in Skomer, Wales, within 13 days, a distance of 5,150 km (3,200 mi).[115] Birds navigate during migration using a variety of methods. For diurnal migrants, the sun is used to navigate by day, and a stellar compass is used at night. Birds that use the sun compensate for the changing position of the sun during the day by the use of an internal clock.[42] Orientation with the stellar compass depends on the position of the constellations surrounding Polaris.[116] These are backed up in some species by their ability to sense the Earth's geomagnetism through specialised photoreceptors.[117]

Communication

See also: Bird vocalization

Birds sometimes use plumage to assess and assert social dominance,[118] to display breeding condition in sexually selected species, or to make threatening displays, as in the Sunbittern's mimicry of a large predator to ward off hawks and protect young chicks.[119] Variation in plumage also allows for the identification of birds, particularly between species. Visual communication among birds may also involve ritualised displays, which have developed from non-signalling actions such as preening, the adjustments of feather position, pecking, or other behaviour. These displays may signal aggression or submission or may contribute to the formation of pair-bonds.[42] The most elaborate displays occur during courtship, where "dances" are often formed from complex combinations of many possible component movements;[120] males' breeding success may depend on the quality of such displays.[121]

Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript disabled or does not have any supported player.

You can download the clip or download a player to play the clip in your browser.

You can download the clip or download a player to play the clip in your browser.

Call of the House Wren, a common North American songbird

Red-billed Queleas, the most numerous species of bird,[127] form enormous flocks—sometimes tens of thousands strong.

Flocking and other associations

While some birds are essentially territorial or live in small family groups, other birds may form large flocks. The principal benefits of flocking are safety in numbers and increased foraging efficiency.[42] Defence against predators is particularly important in closed habitats like forests, where ambush predation is common and multiple eyes can provide a valuable early warning system. This has led to the development of many mixed-species feeding flocks, which are usually composed of small numbers of many species; these flocks provide safety in numbers but increase potential competition for resources.[128] Costs of flocking include bullying of socially subordinate birds by more dominant birds and the reduction of feeding efficiency in certain cases.[129]Birds sometimes also form associations with non-avian species. Plunge-diving seabirds associate with dolphins and tuna, which push shoaling fish towards the surface.[130] Hornbills have a mutualistic relationship with Dwarf Mongooses, in which they forage together and warn each other of nearby birds of prey and other predators.[131]

Resting and roosting

Many sleeping birds bend their heads over their backs and tuck their bills in their back feathers, although others place their beaks among their breast feathers. Many birds rest on one leg, while some may pull up their legs into their feathers, especially in cold weather. Perching birds have a tendon locking mechanism that helps them hold on to the perch when they are asleep. Many ground birds, such as quails and pheasants, roost in trees. A few parrots of the genus Loriculus roost hanging upside down.[138] Some hummingbirds go into a nightly state of torpor accompanied with a reduction of their metabolic rates.[139] This physiological adaptation shows in nearly a hundred other species, including owlet-nightjars, nightjars, and woodswallows. One species, the Common Poorwill, even enters a state of hibernation.[140] Birds do not have sweat glands, but they may cool themselves by moving to shade, standing in water, panting, increasing their surface area, fluttering their throat or by using special behaviours like urohidrosis to cool themselves.

Breeding

See also: Avian reproductive system

Social systems

Like others of its family the male Raggiana Bird of Paradise has elaborate breeding plumage used to impress females.[141]

Other mating systems, including polygyny, polyandry, polygamy, polygynandry, and promiscuity, also occur.[42] Polygamous breeding systems arise when females are able to raise broods without the help of males.[42] Some species may use more than one system depending on the circumstances.

Breeding usually involves some form of courtship display, typically performed by the male.[148] Most displays are rather simple and involve some type of song. Some displays, however, are quite elaborate. Depending on the species, these may include wing or tail drumming, dancing, aerial flights, or communal lekking. Females are generally the ones that drive partner selection,[149] although in the polyandrous phalaropes, this is reversed: plainer males choose brightly coloured females.[150] Courtship feeding, billing and allopreening are commonly performed between partners, generally after the birds have paired and mated.[53]

Homosexual behaviour has been observed in males or females in numerous species of birds, including copulation, pair-bonding, and joint parenting of chicks.[151]

Territories, nesting and incubation

See also: Bird nest

Many birds actively defend a territory from others of the same species during the breeding season; maintenance of territories protects the food source for their chicks. Species that are unable to defend feeding territories, such as seabirds and swifts, often breed in colonies instead; this is thought to offer protection from predators. Colonial breeders defend small nesting sites, and competition between and within species for nesting sites can be intense.[152]All birds lay amniotic eggs with hard shells made mostly of calcium carbonate.[42] Hole and burrow nesting species tend to lay white or pale eggs, while open nesters lay camouflaged eggs. There are many exceptions to this pattern, however; the ground-nesting nightjars have pale eggs, and camouflage is instead provided by their plumage. Species that are victims of brood parasites have varying egg colours to improve the chances of spotting a parasite's egg, which forces female parasites to match their eggs to those of their hosts.[153]

Parental care and fledging

At the time of their hatching, chicks range in development from helpless to independent, depending on their species. Helpless chicks are termed altricial, and tend to be born small, blind, immobile and naked; chicks that are mobile and feathered upon hatching are termed precocial. Altricial chicks need help thermoregulating and must be brooded for longer than precocial chicks. Chicks at neither of these extremes can be semi-precocial or semi-altricial.In some species, both parents care for nestlings and fledglings; in others, such care is the responsibility of only one sex. In some species, other members of the same species—usually close relatives of the breeding pair, such as offspring from previous broods—will help with the raising of the young.[161] Such alloparenting is particularly common among the Corvida, which includes such birds as the true crows, Australian Magpie and Fairy-wrens,[162] but has been observed in species as different as the Rifleman and Red Kite. Among most groups of animals, male parental care is rare. In birds, however, it is quite common—more so than in any other vertebrate class.[42] Though territory and nest site defence, incubation, and chick feeding are often shared tasks, there is sometimes a division of labour in which one mate undertakes all or most of a particular duty.[163]

The point at which chicks fledge varies dramatically. The chicks of the Synthliboramphus murrelets, like the Ancient Murrelet, leave the nest the night after they hatch, following their parents out to sea, where they are raised away from terrestrial predators.[164] Some other species, such as ducks, move their chicks away from the nest at an early age. In most species, chicks leave the nest just before, or soon after, they are able to fly. The amount of parental care after fledging varies; albatross chicks leave the nest on their own and receive no further help, while other species continue some supplementary feeding after fledging.[165] Chicks may also follow their parents during their first migration.[166]

Brood parasites

Main article: Brood parasite

Ecology

The South Polar Skua (left) is a generalist predator, taking the eggs of other birds, fish, carrion and other animals. This skua is attempting to push an Adelie Penguin (right) off its nest

Some nectar-feeding birds are important pollinators, and many frugivores play a key role in seed dispersal.[170] Plants and pollinating birds often coevolve,[171] and in some cases a flower's primary pollinator is the only species capable of reaching its nectar.[172]

Birds are often important to island ecology. Birds have frequently reached islands that mammals have not; on those islands, birds may fulfill ecological roles typically played by larger animals. For example, in New Zealand the moas were important browsers, as are the Kereru and Kokako today.[170] Today the plants of New Zealand retain the defensive adaptations evolved to protect them from the extinct moa.[173] Nesting seabirds may also affect the ecology of islands and surrounding seas, principally through the concentration of large quantities of guano, which may enrich the local soil[174] and the surrounding seas.[175]

A wide variety of Avian ecology field methods, including counts, nest monitoring, and capturing and marking, are used for researching avian ecology.

Relationship with humans

Since birds are highly visible and common animals, humans have had a relationship with them since the dawn of man.[176] Sometimes, these relationships are mutualistic, like the cooperative honey-gathering among honeyguides and African peoples such as the Borana.[177] Other times, they may be commensal, as when species such as the House Sparrow[178] have benefited from human activities. Several bird species have become commercially significant agricultural pests,[179] and some pose an aviation hazard.[180] Human activities can also be detrimental, and have threatened numerous bird species with extinction (hunting, avian lead poisoning, pesticides, roadkill, and predation by pet cats and dogs are common sources of death for birds).Birds can act as vectors for spreading diseases such as psittacosis, salmonellosis, campylobacteriosis, mycobacteriosis (avian tuberculosis), avian influenza (bird flu), giardiasis, and cryptosporidiosis over long distances. Some of these are zoonotic diseases that can also be transmitted to humans.[181]

Economic importance

Domesticated birds raised for meat and eggs, called poultry, are the largest source of animal protein eaten by humans; in 2003, 76 million tons of poultry and 61 million tons of eggs were produced worldwide.[182] Chickens account for much of human poultry consumption, though turkeys, ducks, and geese are also relatively common. Many species of birds are also hunted for meat. Bird hunting is primarily a recreational activity except in extremely undeveloped areas. The most important birds hunted in North and South America are waterfowl; other widely hunted birds include pheasants, wild turkeys, quail, doves, partridge, grouse, snipe, and woodcock.[183] Muttonbirding is also popular in Australia and New Zealand.[184] Though some hunting, such as that of muttonbirds, may be sustainable, hunting has led to the extinction or endangerment of dozens of species.[185]Birds have been domesticated by humans both as pets and for practical purposes. Colourful birds, such as parrots and mynas, are bred in captivity or kept as pets, a practice that has led to the illegal trafficking of some endangered species.[187] Falcons and cormorants have long been used for hunting and fishing, respectively. Messenger pigeons, used since at least 1 AD, remained important as recently as World War II. Today, such activities are more common either as hobbies, for entertainment and tourism,[188] or for sports such as pigeon racing.

Amateur bird enthusiasts (called birdwatchers, twitchers or, more commonly, birders) number in the millions.[189] Many homeowners erect bird feeders near their homes to attract various species. Bird feeding has grown into a multimillion dollar industry; for example, an estimated 75% of households in Britain provide food for birds at some point during the winter.[190]

Religion, folklore and culture

Birds have been featured in culture and art since prehistoric times, when they were represented in early cave paintings.[198] Birds were later used in religious or symbolic art and design, such as the magnificent Peacock Throne of the Mughal and Persian emperors.[199] With the advent of scientific interest in birds, many paintings of birds were commissioned for books. Among the most famous of these bird artists was John James Audubon, whose paintings of North American birds were a great commercial success in Europe and who later lent his name to the National Audubon Society.[200] Birds are also important figures in poetry; for example, Homer incorporated Nightingales into his Odyssey, and Catullus used a sparrow as an erotic symbol in his Catullus 2.[201] The relationship between an albatross and a sailor is the central theme of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which led to the use of the term as a metaphor for a 'burden'.[202] Other English metaphors derive from birds; vulture funds and vulture investors, for instance, take their name from the scavenging vulture.[203]

Perceptions of various bird species often vary across cultures. Owls are associated with bad luck, witchcraft, and death in parts of Africa,[204] but are regarded as wise across much of Europe.[205] Hoopoes were considered sacred in Ancient Egypt and symbols of virtue in Persia, but were thought of as thieves across much of Europe and harbingers of war in Scandinavia.[206]

Conservation

The California Condor once numbered only 22 birds, but conservation measures have raised that to over 300 today.

Main article: Bird conservation

Though human activities have allowed the expansion of a few species, such as the Barn Swallow and European Starling, they have caused population decreases or extinction in many other species. Over a hundred bird species have gone extinct in historical times,[207] although the most dramatic human-caused avian extinctions, eradicating an estimated 750–1800 species, occurred during the human colonisation of Melanesian, Polynesian, and Micronesian islands.[208] Many bird populations are declining worldwide, with 1,227 species listed as threatened by Birdlife International and the IUCN in 2009.[209][210]The most commonly cited human threat to birds is habitat loss.[211] Other threats include overhunting, accidental mortality due to structural collisions or long-line fishing bycatch,[212] pollution (including oil spills and pesticide use),[213] competition and predation from nonnative invasive species,[214] and climate change.

Governments and conservation groups work to protect birds, either by passing laws that preserve and restore bird habitat or by establishing captive populations for reintroductions. Such projects have produced some successes; one study estimated that conservation efforts saved 16 species of bird that would otherwise have gone extinct between 1994 and 2004, including the California Condor and Norfolk Parakeet.[215]

No comments:

Post a Comment