The

Peregrine Falcon (

Falco peregrinus), also known as the

Peregrine,

[2] and historically as the

Duck Hawk in North America,

[3] is a widespread

bird of prey in the

family Falconidae. A large,

crow-sized

falcon, it has a blue-grey back, barred white underparts, and a black head and "moustache". As is typical of

bird-eating raptors, Peregrine Falcons are

sexually dimorphic, females being considerably larger than males.

[4][5] The Peregrine is renowned for its speed, reaching over 322 km/h (200 mph) during its characteristic hunting stoop (high speed dive),

[6] making it the fastest member of the animal kingdom.

[7][8]

The Peregrine's breeding range includes land regions from the

Arctic tundra to the

tropics. It can be found nearly everywhere on Earth, except extreme

polar regions, very high mountains, and most

tropical rainforests; the only major ice-free landmass from which it is entirely absent is

New Zealand. This makes it the world's most widespread raptor

[9] and one of the most widely found bird species. In fact, the only land-based bird species found over a larger geographic area is not always naturally occurring but one widely introduced by humans, the

Rock Pigeon, which in turn now supports many Peregrine populations as a prey species. Both the English and

scientific names of this

species mean "wandering falcon", referring to the

migratory habits of many northern populations. Experts recognize 17 to 19

subspecies which vary in appearance and range; there is disagreement over whether the distinctive

Barbary Falcon is represented by two subspecies of

Falco peregrinus, or is a separate species,

F. pelegrinoides.

While its diet consists almost exclusively of medium-sized birds, the Peregrine will occasionally hunt small mammals, small reptiles, or even insects. Reaching sexual maturity at one year, it mates for life and nests in a

scrape, normally on cliff edges or, in recent times, on tall human-made structures.

[10] The Peregrine Falcon became an endangered species in many areas because of pesticides, especially

DDT. Since the ban on DDT from the early 1970s, populations have recovered, supported by large-scale protection of nesting places and releases to the wild.

[11]

[edit] Description

The Peregrine Falcon has a body length of 34 to 58 centimetres (13–23 in) and a wingspan from 74 to 120 centimetres (29–47 in).

[4][12] The male and female have similar markings and

plumage, but as in many

birds of prey the Peregrine Falcon displays marked reverse

sexual dimorphism in size, with the female measuring up to 30% larger than the male.

[13] Males weigh 424 to 750 grams (0.93–1.7 lb) and the noticeably larger females weigh 910 to 1,500 grams (2.0–3.3 lb); for variation in weight between subspecies, see below. The standard linear measurements of Peregrines are: the wing chord measures 26.5–39 cm (10.4–15 in), the tail measures 13–19 cm (5.1–7.5 in) and the tarsus measures 4.5 to 5.6 cm (1.8 to 2.2 in).

[14]

The back and the long pointed wings of the adult are usually bluish black to slate grey with indistinct darker barring (see "Subspecies"

below); the wingtips are black.

[12] The white to rusty underparts are barred with thin clean bands of dark brown or black.

[15] The tail, coloured like the back but with thin clean bars, is long, narrow, and rounded at the end with a black tip and a white band at the very end. The top of the head and a "moustache" along the cheeks are black, contrasting sharply with the pale sides of the neck and white throat.

[16] The

cere is yellow, as are the feet, and the

beak and

claws are black.

[17] The upper beak is notched near the tip, an

adaptation which enables falcons to kill prey by severing the

spinal column at the neck.

[4][5][6] The immature bird is much browner with streaked, rather than barred, underparts, and has a pale bluish cere and orbital ring.

[4]

[edit] Taxonomy and systematics

Falco peregrinus was first described under its current binomial name by English ornithologist

Marmaduke Tunstall in his 1771 work

Ornithologia Britannica.

[18] The scientific name

Falco peregrinus is a

Medieval Latin phrase that was used by

Albertus Magnus in 1225. The specific name taken from the fact that juvenile birds were taken while journeying to their breeding location rather than from the nest, as falcon nests were difficult to get at.

[19] The Latin term for falcon,

falco, is related to

falx, the Latin word meaning

sickle, in reference to the silhouette of the falcon's long, pointed wings in flight.

[6]

The Peregrine Falcon belongs to a

genus whose lineage includes the

hierofalcons[20] and the

Prairie Falcon (

F. mexicanus). This lineage probably diverged from other falcons towards the end of the

Late Miocene or in the

Early Pliocene, about 5-8

million years ago (mya). As the Peregrine-hierofalcon group includes both

Old World and North American species, it is likely that the lineage originated in western

Eurasia or Africa. Its relationship to other falcons is not clear; the issue is complicated by widespread

hybridization confounding

mtDNA sequence analyses; for example a genetic lineage of the

Saker Falcon (

F. cherrug) is known

[21] which originated from a male Saker producing fertile young with a female Peregrine ancestor, and the descendants further breeding with Sakers.

[22]

Today, Peregrines are regularly paired in captivity with other species such as the

Lanner Falcon (

F. biarmicus) to produce the "

perilanner", a somewhat popular bird in

falconry as it combines the Peregrine's hunting skill with the Lanner's hardiness, or the

Gyrfalcon to produce large, strikingly coloured birds for the use of falconers. As can be seen, the Peregrine is still genetically close to the hierofalcons, though their lineages diverged in the

Late Pliocene (maybe some 2.5–2 mya in the

Gelasian).

[23]

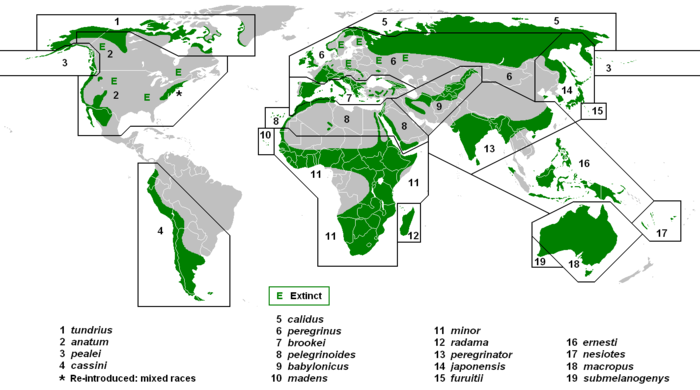

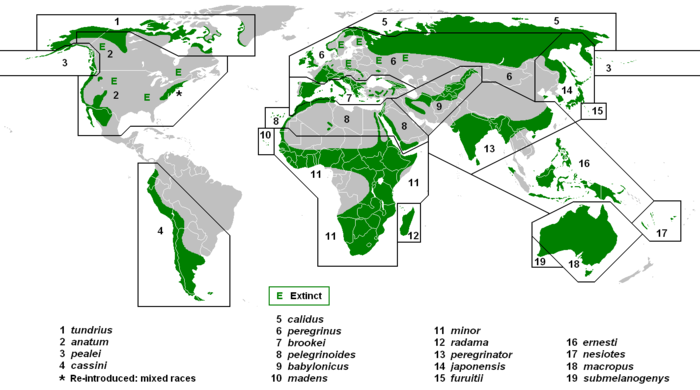

[edit] Subspecies

Numerous

subspecies of

Falco peregrinus have been described, with 19 accepted by the 1994

Handbook of the Birds of the World,

[4][5][24] which considers the

Barbary Falcon of the

Canary Islands and coastal north

Africa to be two subspecies

(pelegrinoides and

babylonicus) of

Falco peregrinus, rather than a distinct species,

F. pelegrinoides. The following map shows the general ranges of these 19 subspecies:

Breeding ranges of the subspecies

- Falco peregrinus anatum, described by Bonaparte in 1838,[25] is known as the American Peregrine Falcon, or "Duck Hawk"; its scientific name means "Duck Peregrine Falcon". At one time, it was partly included in leucogenys. It is mainly found in the Rocky Mountains today. It was formerly common throughout North America between the tundra and northern Mexico, where current reintroduction efforts seek to restore the population.[25] Most mature anatum, except those that breed in more northern areas, winter in their breeding range. Most vagrants that reach western Europe seem to belong to the more northern and strongly migratory tundrius, only considered distinct since 1968. It is similar to peregrinus but is slightly smaller; adults are somewhat paler and less patterned below, but juveniles are darker and more patterned below. Males weigh 500 to 700 grams (1.1–1.5 lb), while females weigh 800 to 1,100 grams (1.8–2.4 lb).[26] It has become extinct in eastern North America, and populations there are hybrids as a result of reintroductions of birds from elsewhere.[27]

Adult of subspecies

pealei or

tundrius by its nest in

Alaska

- Falco peregrinus babylonicus, described by P.L. Sclater in 1861, is found in eastern Iran along the Hindu Kush and Tian Shan to Mongolian Altai ranges. A few birds winter in northern and northwestern India, mainly in dry semi-desert habitats.[28] It is paler than pelegrinoides, and somewhat similar to a small, pale Lanner Falcon (Falco biarmicus). Males weigh 330 to 400 grams (12 to 14 oz), while females weigh 513 to 765 grams (18.1 to 27.0 oz).[5]

- Falco peregrinus brookei, described by Sharpe in 1873, is also known as the Mediterranean Peregrine Falcon or the Maltese Falcon.[29] It includes caucasicus and most specimens of the proposed race punicus, though others may be pelegrinoides, Barbary Falcons (see also below), or perhaps the rare hybrids between these two which might occur around Algeria. They occur from the Iberian Peninsula around the Mediterranean, except in arid regions, to the Caucasus. They are non-migratory. It is smaller than the nominate subspecies, and the underside usually has rusty hue.[15] Males weigh around 445 grams (0.98 lb), while females weigh up to 920 grams (2.0 lb).[5]

- Falco peregrinus calidus, described by John Latham in 1790, was formerly called leucogenys and includes caeruleiceps. It breeds in the Arctic tundra of Eurasia, from Murmansk Oblast to roughly Yana and Indigirka Rivers, Siberia. It is completely migratory, and travels south in winter as far as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. It is often seen around wetland habitats.[30] It is paler than peregrinus, especially on the crown. Males weigh 588 to 740 grams (1.30–1.6 lb), while females weigh 925 to 1,333 grams (2.04–2.94 lb).[5]

- Falco peregrinus cassini, described by Sharpe in 1873, is also known as the Austral Peregrine Falcon. It includes kreyenborgi, the Pallid Falcon[31] a leucistic morph occurring in southernmost South America, which was long believed to be a distinct species.[32] Its range includes South America from Ecuador through Bolivia, northern Argentina, and Chile to Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Islands.[15] It is non-migratory. It is similar to nominate, but slightly smaller with a black ear region. The variation kreyenborgi is medium grey above, has little barring below, and has a head pattern like the Saker Falcon, but the ear region is white.[32]

- Falco peregrinus ernesti, described by Sharpe in 1894, is found from Indonesia to Philippines and south to Papua New Guinea and the nearby Bismarck Archipelago. Its geographical separation from nesiotes requires confirmation. It is non-migratory. It differs from the nominate subspecies in the very dark, dense barring on its underside and its black ear coverts.

- Falco peregrinus furuitii, described by Momiyama in 1927, is found on the Izu and Ogasawara Islands south of Honshū, Japan. It is non-migratory. It is very rare, and may only remain on a single island.[4] It is a dark form, resembling pealei in colour, but darker, especially on tail.[15]

- Falco peregrinus japonensis, described by Gmelin in 1788, includes kleinschmidti, pleskei, and harterti, and seems to refer to intergrades with calidus. It is found from northeast Siberia to Kamchatka (though it is possibly replaced by pealei on the coast there) and Japan. Northern populations are migratory, while those of Japan are resident. It is similar to peregrinus, but the young are even darker than those of anatum.

F. p. macropus, Australia

- Falco peregrinus macropus, described by Swainson in 1837, is the Australian Peregrine Falcon. It is found in Australia in all regions except the southwest. It is non-migratory. It is similar to brookei in appearance, but is slightly smaller and the ear region is entirely black. The feet are proportionally large.[15]

- Falco peregrinus madens, described by Ripley and Watson in 1963, is unusual in having some sexual dichromatism. If the Barbary Falcon (see below) is considered a distinct species, it is sometimes placed therein. It is found in the Cape Verde Islands, and is non-migratory;[15] it is endangered with only six to eight pairs surviving.[4] Males have a rufous wash on crown, nape, ears, and back; underside conspicuously washed pinkish-brown. Females are tinged rich brown overall, especially on the crown and nape.[15]

- Falco peregrinus minor, first described by Bonaparte in 1850. It was formerly often perconfusus.[33] It is sparsely and patchily distributed throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa and widespread in Southern Africa. It apparently reaches north along the Atlantic coast as far as Morocco. It is non-migratory, crow-sized, and dark coloured.

Captive

Falco peregrinus pealei

- Falco peregrinus pealei, described by Ridgway in 1873, is also known as Peale's Falcon, and includes rudolfi.[36] It is found in the Pacific Northwest of North America, northwards from the Puget Sound along the British Columbia coast (including the Queen Charlotte Islands), along the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands to the far eastern Bering Sea coast of Russia,[36] and may also occur on the Kuril Islands and the coasts of Kamchatka. It is non-migratory. It is the largest subspecies, and it looks like an oversized and darker tundrius or like a strongly barred and large anatum. The bill is very wide.[37] Juveniles occasionally have pale crowns. Males weigh 700 to 1,000 grams (1.5–2.2 lb), while females weigh 1,000 to 1,500 grams (2.2–3.3 lb).[26]

- Falco peregrinus pelegrinoides, first described by Temminck in 1829, is found in the Canary Islands through north Africa and the Near East to Mesopotamia. It is most similar to brookei, but is markedly paler above, with a rusty neck, and is a light buff with reduced barring below. It is smaller than the nominate subspecies; females weigh around 610 grams (1.3 lb).[5]

- Falco peregrinus peregrinator, described by Sundevall in 1837, is known as the Indian Peregrine Falcon, Black Shaheen, Indian Shaheen [38] or Shaheen Falcon.[39] It was formerly sometimes known as Falco atriceps or Falco shaheen. Its range includes South Asia from Pakistan across India and Bangladesh to Sri Lanka and Southeastern China. In India, the Shaheen is reported from all states except Uttar Pradesh, mainly from rocky and hilly regions. The Shaheen is also reported from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal.[28] It has a clutch size of 3 to 4 eggs, with the chicks fledging time of 48 days with an average nesting success of 1.32 chicks per nest. In India, apart from nesting on cliffs, it has also been recorded as nesting on man-made structures such as buildings and cellphone transmission towers.[28] A population estimate of 40 breeding pairs in Sri Lanka was made in 1996.[40] It is non-migratory, and is small and dark, with rufous underparts. In Sri Lanka this species is found to favour the higher hills while the migrant calidus is more often seen along the coast.[41]

- Falco peregrinus peregrinus, the nominate (first-named) subspecies, described by Tunstall in 1771, breeds over much of temperate Eurasia between the tundra in the north and the Pyrenees, Mediterranean region and Alpide belt in the south.[25] It is mainly non-migratory in Europe, but migratory in Scandinavia and Asia. Males weigh 580 to 750 grams (1.3–1.7 lb), while females weigh 925 to 1,300 grams (2.04–2.9 lb).[5] It includes brevirostris, germanicus, rhenanus, and riphaeus.

- Falco peregrinus submelanogenys, described by Mathews in 1912, is the Southwest Australian Peregrine Falcon. It is found in southwest Australia and is non-migratory.

- Falco peregrinus tundrius, described by C.M. White in 1968, was at one time included in leucogenys It is found in the Arctic tundra of North America to Greenland, and migrates to wintering grounds in Central and South America.[37] Most vagrants that reach western Europe belong to this subspecies, which was previously united with anatum. It is the New World equivalent to calidus. It is smaller than anatum. It is also paler than anatum; most have a conspicuous white forehead and white in ear region, but the crown and "moustache" are very dark, unlike in calidus.[37] Juveniles are browner, and less grey, than in calidus, and paler, sometimes almost sandy, than in anatum. Males weigh 500 to 700 grams (1.1–1.5 lb), while females weigh 800 to 1,100 grams (1.8–2.4 lb).[26]

[edit] Barbary Falcon

Main article:

Barbary Falcon

Two of the subspecies listed above (

Falco peregrinus pelegrinoides and

F. p. babylonicus) are often instead treated together as a distinct

species,

Falco pelegrinoides (

Barbary Falcon),

[5] although they were included within

F. peregrinus in the 1994

Handbook of the Birds of the World.

[4] These birds inhabit

arid regions from the

Canary Islands along the rim of the

Sahara through the

Middle East to

Central Asia and

Mongolia.

Barbary Falcons have a red neck patch but otherwise differ in appearance from the Peregrine proper merely according to

Gloger's Rule, relating

pigmentation to

environmental humidity.

[42] The Barbary Falcon has a peculiar way of flying, beating only the outer part of its wings like

fulmars sometimes do; this also occurs in the Peregrine, but less often and far less pronounced.

[5] The Barbary Falcon's

shoulder and

pelvis bones are stout by comparison with the Peregrine, and its feet are smaller.

[43] Barbary Falcons breed at different times of year than neighboring Peregrine Falcon subspecies,

[5][24][44][45][46][47][48] but there are no postzygotic reproduction barriers in place.

[49] There is a 0.6–0.7% genetic distance in the Peregine-Barbary Falcon ("peregrinoid") complex.

[44]

Another subspecies of

Falco peregrinus, madens, has also sometimes been treated instead within a separately recognized

F. pelegrinoides.[15]

[edit] See also

- Perlin, a hybrid of the Peregrine and the Merlin (Falco columbarius)

[edit] Ecology and behavior

Closeup of head showing nostril tubercle

Silhouette in normal flight (left) and at the start of a stoop

The Peregrine Falcon lives mostly along

mountain ranges,

river valleys,

coastlines, and increasingly in

cities.

[15] In mild-winter regions, it is usually a permanent resident, and some individuals, especially adult males, will remain on the breeding territory. Only populations that breed in Arctic

climes typically migrate great distances during the northern winter.

[50]

The Peregrine Falcon reaches faster speeds than any other animal on the planet when performing the stoop,

[7] which involves soaring to a great height and then diving steeply at speeds of over 320 km/h (200 mph), hitting one wing of its prey so as not to harm itself on impact.

[6] The air pressure from a 200 mph (320 km/h) dive could possibly damage a bird's

lungs, but small bony tubercles on a falcon's nostrils guide the powerful airflow away from the nostrils, enabling the bird to breathe more easily while diving by reducing the change in air pressure.

[51] To protect their eyes, the falcons use their

nictitating membranes (third eyelids) to spread tears and clear debris from their eyes while maintaining vision. A study testing the flight physics of an "ideal falcon" found a theoretical speed limit at 400 km/h (250 mph) for low altitude flight and 625 km/h (390 mph) for high altitude flight.

[52] In 2005, Ken Franklin recorded a falcon stooping at a top speed of 389 km/h (242 mph).

[53] A video of one of the dives can be seen in

this link.

The life span of Peregrine Falcons in the wild is up to 15.5 years.

[5] Mortality in the first year is 59–70%, declining to 25–32% annually in adults.

[5] Apart from such

anthropogenic threats as collision with human-made objects, the Peregrine may be killed by

eagles or large

owls.

[54]

The Peregrine Falcon is

host to a range of

parasites and

pathogens. It is a

vector for

Avipoxvirus,

Newcastle disease virus,

Falconid herpesvirus 1 (and possibly other

Herpesviridae), and some

mycoses and

bacterial infections.

Endoparasites include

Plasmodium relictum (usually not causing

malaria in the Peregrine Falcon),

Strigeidae trematodes,

Serratospiculum amaculata (

nematode), and

tapeworms. Known Peregrine Falcon

ectoparasites are

chewing lice,

[55] Ceratophyllus garei (a

flea), and

Hippoboscidae flies (

Icosta nigra,

Ornithoctona erythrocephala).

[56]

[edit] Feeding

An immature Peregrine eating its prey on the deck of a ship

The Peregrine Falcon feeds almost exclusively on medium-sized birds such as

pigeons and doves,

waterfowl,

songbirds, and

waders.

[17] Worldwide, it is estimated that between 1,500 and 2,000 bird species (up to roughly a fifth of the world's bird species) are predated somewhere by these falcons. In

North America, prey has varied in size from 3-g

hummingbirds to a 3.1-kg

Sandhill Crane (killed by a peregrine in a swoop).

[57] Smaller raptors are regularly predated, including smaller falcons such as the

American Kestrel.

[58] In urban areas, the main component of the Peregrine's diet is the

Rock or

Feral Pigeon, which comprise 80% or more of the dietary intake for peregrines in some cities. Other common city birds are also taken regularly, including

Mourning Doves,

Common Wood Pigeons,

Common Swifts,

Northern Flickers,

Common Starlings,

American Robins,

Common Blackbirds, and

corvids (such as

magpies or

Carrion,

House, and

American Crows).

[59] Other than bats taken at night,

[59] the Peregrine rarely hunts mammals, but will on occasion take small species such as

rats,

voles,

hares,

shrews,

mice and

squirrels. Coastal populations of the large subspecies

pealei feed almost exclusively on

seabirds.

[16] In the Brazilian

mangrove swamp of

Cubatão, a wintering falcon of the subspecies

tundrius was observed while successfully hunting a juvenile

Scarlet Ibis.

[60] Insects and reptiles make up a small proportion of the diet, which varies greatly depending on what prey is available.

[17]

The Peregrine Falcon hunts at dawn and dusk, when prey are most active, but also nocturnally in cities, particularly during migration periods when hunting at night may become prevalent. Nocturnal migrants taken by Peregrines include species as diverse as

Yellow-billed Cuckoo,

Black-necked Grebe,

Virginia Rail, and

Common Quail.

[59] The Peregrine requires open space in order to hunt, and therefore often hunts over open water,

marshes,

valleys, fields, and

tundra, searching for prey either from a high perch or from the air.

[61] Large congregations of migrants, especially species that gather in the open like

shorebirds, can be quite attractive to hunting Peregrines. Once prey is spotted, it begins its stoop, folding back the tail and wings, with feet tucked.

[16] Prey is struck and captured in mid-air; the Peregrine Falcon strikes its prey with a clenched foot, stunning or killing it with the impact, then turns to catch it in mid-air.

[61] If its prey is too heavy to carry, a Peregrine will drop it to the ground and eat it there. Prey is plucked before consumption.

[51]

[edit] Reproduction

The Peregrine Falcon is sexually mature at one to three years of age, but in healthy populations they breed after two to three years of age. A pair mates for life and returns to the same nesting spot annually. The courtship flight includes a mix of aerial acrobatics, precise spirals, and steep dives.

[12] The male passes prey it has caught to the female in mid-air. To make this possible, the female actually flies upside-down to receive the food from the male's talons.

During the breeding season, the Peregrine Falcon is territorial; nesting pairs are usually more than 1 km (0.62 mi) apart, and often much farther, even in areas with large numbers of pairs.

[62] The distance between nests ensures sufficient food supply for pairs and their chicks. Within a breeding territory, a pair may have several nesting ledges; the number used by a pair can vary from one or two to seven in a 16 year period.

The Peregrine Falcon nests in a scrape, normally on cliff edges. The female chooses a nest site, where she scrapes a shallow hollow in the loose soil, sand, gravel, or dead vegetation in which to lay eggs. No nest materials are added.

[12] Cliff nests are generally located under an overhang, on ledges with vegetation, and south-facing sites are favored.

[16] In some regions, as in parts of

Australia and on the west coast of Northern North America, large tree hollows are used for nesting. Before the demise of most European peregrines, a large population of peregrines in central and western Europe used the disused nests of other large birds.

[17] In remote, undisturbed areas such as the Arctic, steep slopes and even low rocks and mounds may be used as nest sites. In many parts of its range, Peregrines now also nest regularly on tall buildings or bridges; these human-made structures used for breeding closely resemble the natural cliff ledges that the Peregrine prefers for its nesting locations.

[4][62]

The pair defends the chosen nest site against other Peregrines, and often against

ravens,

herons, and

gulls, and if ground-nesting, also such mammals as

foxes,

wolverines,

felids,

bears and

wolves.

[62] Both nests and (less frequently) adults are predated by larger-bodied raptorial birds like

eagles, large

owls, or

Gyrfalcons. Peregrines defending their nests have managed to kill raptors as large as

Golden Eagles and

Bald Eagles (both of which they normally avoid as potential predators) that have come too close to the nest.

[63]

The date of egg-laying varies according to locality, but is generally from February to March in the

Northern Hemisphere, and from July to August in the

Southern Hemisphere, although the Australian subspecies

macropus may breed as late as November, and

equatorial populations may nest anytime between June and December. If the eggs are lost early in the nesting season, the female usually lays another clutch, although this is extremely rare in the Arctic due to the short summer season. Generally three to four eggs, but sometimes as few as one or as many as five, are laid in the scrape.

[64] The eggs are white to buff with red or brown markings.

[64] They are incubated for 29 to 33 days, mainly by the female,

[16] with the male also helping with the incubation of the eggs during the day, but only the female incubating them at night. The average number of young found in nests is 2.5, and the average number that fledge is about 1.5, due to the occasional production of infertile eggs and various natural losses of nestlings.

[4][51][54]

After hatching, the chicks (called "eyases"

[65]) are covered with creamy-white down and have disproportionately large feet.

[62] The male (called the "tiercel") and the female (simply called the "falcon") both leave the nest to gather prey to feed the young.

[51] The hunting territory of the parents can extend a radius of 19 to 24 km (12–15 miles) from the nest site.

[66] Chicks

fledge 42 to 46 days after hatching, and remain dependent on their parents for up to two months.

[67]

[edit] Relationship with humans

[edit] Falconry

The Peregrine Falcon has been used in

falconry for more than 3,000 years, beginning with nomads in central Asia.

[62] Due to its ability to dive at high speeds, it is highly sought-after and generally used by experienced falconers.

[13] Peregrine Falcons are also occasionally used to scare away birds at airports to reduce the risk of

bird-plane strikes, improving air-traffic safety,

[68] and were used to intercept homing pigeons during World War II.

[69]

Peregrine Falcons have been successfully bred in captivity, both for falconry and for release back into the wild.

[70] Until 2004 nearly all Peregrines used for falconry in the US were captive-bred from the progeny of falcons taken before the US

Endangered Species Act was enacted and from those few infusions of wild genes available from Canada and special circumstances. Peregrine Falcons were removed from the United States' endangered species list in 1999. The successful recovery program was aided by the effort and knowledge of falconers – in collaboration with

The Peregrine Fund and state and federal agencies – through a technique called

hacking. Finally, after years of close work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a limited take of wild Peregrines was allowed in 2004, the first wild Peregrines taken specifically for falconry in over 30 years. Since Peregrine eggs and chicks are still often targeted by illegal collectors,

[71] it is common practice not to publicize unprotected nest locations.

[72]

[edit] Decline due to pesticides

The Peregrine Falcon became an endangered species because of the use of

organochlorine pesticides, especially

DDT, during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

[73] Pesticide

biomagnification caused

organochlorine to build up in the falcons' fat tissues, reducing the amount of calcium in their eggshells. With thinner shells, fewer falcon eggs survived to hatching.

[61][74] In several parts of the world, such as the eastern

United States and

Belgium, this species became

extirpated (locally extinct) as a result.

[67] An alternate point of view is that populations in the eastern North America had vanished due to hunting and egg collection.

[27]

[edit] Recovery efforts

In the

United States,

Canada,

Germany and

Poland, wildlife services in Peregrine Falcon recovery teams breed the species in captivity.

[75] The chicks are usually fed through a chute or with a

hand puppet mimicking a Peregrine's head, so they cannot see to

imprint on the human trainers.

[50] Then, when they are old enough, the rearing box is opened, allowing the bird to train its wings. As the fledgling gets stronger, feeding is reduced forcing the bird to learn to hunt. This procedure is called

hacking back to the wild.

[76] To release a captive-bred falcon, the bird is placed in a special cage at the top of a tower or cliff ledge for some days or so, allowing it to acclimate itself to its future environment.

[76]

Worldwide recovery efforts have been remarkably successful.

[75] The widespread restriction of DDT use eventually allowed released birds to breed successfully.

[50] The Peregrine Falcon was removed from the

U.S. Endangered Species list on August 25, 1999.

[50][77]

Some controversy has existed over the origins of captive breeding stock used by

The Peregrine Fund in the recovery of peregrine falcons throughout the contiguous United States. Several peregrine subspecies were included in the breeding stock, including birds of Eurasian origin. Due to the

extirpation of the Eastern

anatum (

Falco peregrinus anatum), the near extirpation of the

anatum in the Midwest, and the limited gene pool within North American breeding stock, the inclusion of non-native

subspecies was justified to optimize the

genetic diversity found within the species as a whole.

[78]

[edit] The Peregrine by J A Baker

This book by

John Alec Baker [79] [80]was first published in 1967 and recounts in diary form his observations of peregrines (and their interaction with other birds) near his home in

Chelmsford, Essex, England, over a single winter from October to April (probably the very cold winter of 1962/3). It is widely regarded as masterpiece of nature writing.

Mark Cocker, for example, regards the book as

one of the most outstanding books on nature in the twentieth century[81]. Cocker continues

There is an occasional metaphysical density to the language, but more often he (Baker) described the falcon's actions in passages of radiant lyricism that both express his own burning obession and restate all the qualities that make the bird such a totem species.

[edit] Current status

Populations of the Peregrine Falcon have bounced back in most parts of the world. In

Britain, there has been a recovery of populations since the crash of the 1960s. This has been greatly assisted by conservation and protection work led by the

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The RSPB has estimated that there are 1,402 breeding pairs in the UK.

[82][83] Peregrines now breed in many mountainous and coastal areas, especially in the west and north, and nest in some urban areas, capitalising on the urban

Feral Pigeon populations for food.

[84] In many parts of the world Peregrine Falcons have adapted to urban habitats, nesting on

cathedrals,

skyscraper window ledges, tower blocks,

[85] and the towers of

suspension bridges. Many of these nesting birds are encouraged, sometimes gathering media attention and often monitored by cameras.

[86][87]

[edit] Cultural significance

Due to its striking hunting technique, the Peregrine has often been associated with aggression and martial prowess. Native Americans of the

Mississippian culture (c. 800–1500) used the Peregrine, along with other several birds of prey, in imagery as a symbol of "aerial (celestial) power" and buried men of high status in costumes associating to the ferocity of "raptorial" birds.

[88] In the

late Middle Ages, the Western European nobility that used Peregrines for hunting, considered the bird associated with

princes in formal hierarchies of birds of prey, just below the

Gyrfalcon associated with

kings. It was considered "a royal bird, more armed by its courage than its claws". Terminology used by Peregrine breeders also used the

Old French term

gentil, "of noble birth; aristocratic", particularly with the Peregrine.

[89]

The Peregrine Falcon is the

national animal of the

United Arab Emirates. Since 1927, the Peregrine Falcon has been the official mascot of

Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, Ohio.

[90] The 2007 U.S.

Idaho state quarter features a Peregrine Falcon.

[91]